and whanne they had receiued holy bapteme Seint George drewe oute his suerde and slowe þe dragon and comaunded that he shuld be born oute of the citee

- The Gilte Legende

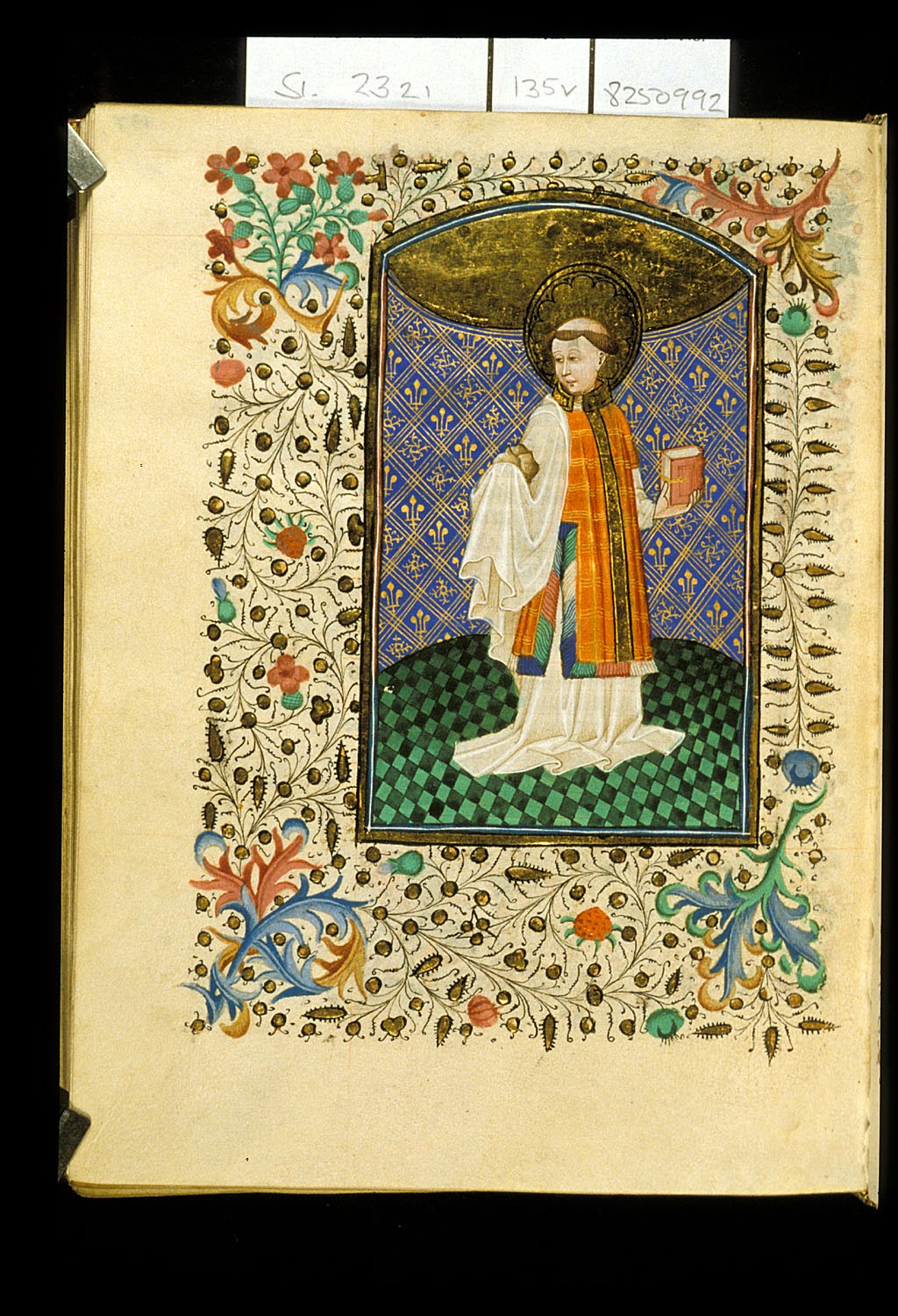

George and the dragon

Chambéry - BM - ms. 0004, Franciscan brevairy, c.1430

Courtesy of Enluminures

In my previous blogpost I presented the legend of St George as it is rendered in The Old English Martyrology, a version which appears to antedate the slaying of the dragon, which today is the most famous episode in his story. The Old English narrative focusses instead solely on his martyrdom and on his ability to posthumously bring about miraculous cures. However, an important part of the legend of St George is that he was a missionary saint, and the story of the dragon follows - as shown in the epigraph - a mass conversion. This motif is well-known in Christian hagiography and pits the power of God funnelled through the saint against the image of the arch-enemy Satan. A similar story is known of Pope Sylvester, for instance, who faced the pestiferous dragon beneath Rome. The dragon is thus an important aspect of the George story, since it is tied up to his feats as an apostle.

In The Old English Martyrology, as stated, nothing is said of George as a missionary, at least not in the text for his feast-day, April 23. Curiously enough, however, an allusion to this aspect of George's vita is in fact mentioned in the martyrology, but in another story, the story of Queen Alexandria. Alexandria is here said to be the wife of the (non-historical) pagan emperor Datianus, who is the main antagonist in the story of St George, as he is in the legend of his newly-converted wife. Why there is no reference to the other story in either of these texts is not clear, but may support Christine Rauer's suggestion that the compiler of the martyrology wrote the texts not chronologically but according to what sources he had available at a given time (Rauer 2013: 11ff). Hence, it is possible that although the stories of George and Alexandria are related, they have reached the martyrologist through different texts.

Alexandria is not a well-known saint in the high-medieval west, and she is not included in Legenda Aurea. Below I will give her story as rendered in The Old English Martyrology.

On the twenty-seventh day of the month is the feast of the holy queen St Alexandria; she was the queen of the pagan emperor Datianus, who was the head of all earthly Kings. But she believed in God through the teaching of the martyr St George. When the emperor realised that, that she believed in God, he said: 'Woe is me, Alexandria; you are bewitched by the tricks of George. Why are you destroying my authority. Or why are you leaving me?' When he could not change her mind with his words, he had her suspended by her hair and punished with various tortures. When he could not overcome her with those, he had her led away to be beheaded. Then she asked her executioners that they should giver her a little more time. Then she went to her palatium, that is to her hall, and lifted up her eyes to heaven and said: 'See, Lord, that I now leave my hall open with all my treasures for your holy name. But you, my Saviour, open now your paradise to me.' And then she fulfilled her martyrdom with faith in Christ.

%2B-%2BChamb%C3%A9ry%2B-%2BBM%2B-%2Bms.%2B0004%2C%2BFranciscan%2Bbrevairy%2C%2Bc.1430%2B(from%2Benluminures).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

%2Band%2BAgnes%2C%2B1747-48%2C%2BJesuit%2Bchurch%2Bof%2BSanta%2BMaria%2Bdel%2BRosario%2C%2BVenice%2B(courtesy%2Bof%2BSch%C3%A4fer%2C%2B%C3%96kumenisches%2BHeiligenlexikon).jpg)