And was the holy Lamb of God,

On Englands pleasant pastures seen!

- And did those feet, William Blake

On Englands pleasant pastures seen!

- And did those feet, William Blake

fredag 25. mars 2016

Upon the Annunciation and Passion falling on one day, by John Donne

March 25 is a day of great importance in the Christian calendar since it is celebrated as the feast of the Annunciation, when Gabriel the Archangel visited Mary and announced that she would carry the son of God. It is commonly held that Christ was immaculately conceived in this episode from the Gospel of Luke, chapter 2, which is daily rehearsed in the liturgical office as the Magnificat. The Annunciation has been a feast of high status throughout Christian history, and even after the Reformation it was celebrated in Protestant countries. In Norway, for instance, the feast is known as "Maria bodskapsdag" (in Nynorsk) or "Bebudelsen" (in Bokmål), meaning the day of Mary's message.

This year, however, March 25 has a double importance as it is also Good Friday, the day of Christ's crucifixion, one of the two most important events in the Christian salvation story. That these two celebrations are conjoined in one and the same day is of great mystical importance to a Christian, as it is possible to commemorate both the conception and the death of Christ, both the beginning and the end of his life as a man on earth (save a short while after the Resurrection).

This combination of feasts is a rare occurrence, and I was first notified of it via a recent blogpost on the excellent blog Clerk of Oxford. For the details I will therefore refer you to the Clerk's exposition. In the Clerk's blogpost, however, I was made aware of a poem by John Donne which he wrote when the same confluence occurred in 1608. Being immensely fond of John Donne's poetry, I've read the verse twice today, and I'm presenting it to you here so that you can share the brilliance that is Donne.

Upon the Annunciation and Passion falling on one day

1608

Tamely frail body' abstain today; today

My soul eats twice, Christ hither and away.

She sees him man, so like God made in this,

That of them both a circle emblem is,

Whose first and last concur; this doubtful day

Of feast or fast, Christ came, and went away;

She sees him nothing twice at once, who is all;

She sees a cedar plant itself, and fall,

Her maker put to making, and the head

Of life, at once, not yet alive, and dead;

She sees at once the virgin mother stay

Reclused at home, public at Golgotha.

Sad and rejoiced she's seen at once, and seen

At almost fifty, and at scarce fifteen.

At once a son is promised her, and gone,

Gabriel gives Christ to her, he her to John;

Not fully a mother, she's in orbity,

At once receiver and the legacy;

All this, and all between, this day hath shown,

Th'abridgement of Christ's story, which makes one

(As in plain maps, the furthest west is east)

Of the angel's Ave, 'and Consummatum est.

How well the Church, God's court of faculties

Deals, in sometimes, and seldom joining these;

As by the self-fixed pole we never do

Direct our course, but the next star thereto,

Which shows where the 'other is, and which we say

(Because it strays not far) doth never stray;

So God by his Church, nearest to him, we know

And stand firm, if we by her motion go;

His Spirit, as his fiery pillar doth

Lead, and his Church, as cloud; to one end both:

This Church, by letting these days join, hath shown

Death and conception in mankind is one:

Or 'twas in him the same humility,

That he would be a man, and leave to be:

Or as creation he had made, as God,

With the last judgement, but one period,

His imitating spouse would join in one

Manhood's extremes: he shall come, he is gone:

Or as though one blood drop, which thence did fall,

Accepted, would have served, he yet shed all;

So though the least of his pains, deeds, or words,

Would busy a life, she all this day affords;

This treasure then, in gross, my soul uplay,

And in my life retail it every day.

Here taken from Carey, John (ed.), John Donne - the Major Works, Oxford World's Classics, 1990: 155-56.

Etiketter:

John Donne,

Liturgy,

Norway,

Poetry,

Religion

torsdag 24. mars 2016

Saint Wilfrid and the Easter controversy

In the Christian year, the celebration of Easter is the mystical climax and the most important feast of the annual cycle. Since Easter is a movable feast there have been many debates throughout the early Christian centuries about when the feast should be celebrated, and there have been many attempts at calculating a calendar cycle that would accurately predict the time of Easter.

One of the arguably best known examples of this ongoing Easter controversy took place in England at the Synod of Whitby in 664, where representatives of the Celtic and the Roman churches presented their arguments for their respective views. The story is perhaps most famously recorded in Bede's Ecclesiastical History, book III, chapter 25, but it is also expounded in dramatic detail in the Life of Wilfrid written by Eddius Stephanus in 720. Wilfrid (d.709) was a monk from Lindisfarne who studied in Rome and became bishop of York, and he was among the representatives from the Roman church at the Synod in 664. In the account by Eddius Stephanus' it is Wilfrid who single-handedly is responsible for the victory of the Roman party and the introduction of the Roman calculation in all of Britain.

I will not go into great detail here regarding the Synod of Whitby (an introduction can be found here). Suffice it to say that the matter was one of great importance, since there were in Britain at that time two competing Christian traditions. The Celtic church had its origin in the Roman era and had established its own missionary tradition which had founded centres on the Continent, and which had a strong influence in the north of England. The other side is referred to as the Roman side since it had been established by the missionary work from Rome as ordered by Pope Gregory the Great. At Whitby, therefore, not only correct religious observance - itself an important issue - but also ecclesiastical power struggles were at play.

As an overview of this event and as a reminder of the importance of Easter, I will here quote from J. F. Webb's translation of Eddius Stephanus' Life of Wilfrid, published in The Age of Bede, Penguin Classics, 2004: 116-17. The account is found in chapter 10. Eddius' introductory information about Bishop Colman is largely incorrect (see Webb 2004: 116). It is also worth noting that this takes place before Wilfrid ascended to the episcopacy of York.

One of the arguably best known examples of this ongoing Easter controversy took place in England at the Synod of Whitby in 664, where representatives of the Celtic and the Roman churches presented their arguments for their respective views. The story is perhaps most famously recorded in Bede's Ecclesiastical History, book III, chapter 25, but it is also expounded in dramatic detail in the Life of Wilfrid written by Eddius Stephanus in 720. Wilfrid (d.709) was a monk from Lindisfarne who studied in Rome and became bishop of York, and he was among the representatives from the Roman church at the Synod in 664. In the account by Eddius Stephanus' it is Wilfrid who single-handedly is responsible for the victory of the Roman party and the introduction of the Roman calculation in all of Britain.

I will not go into great detail here regarding the Synod of Whitby (an introduction can be found here). Suffice it to say that the matter was one of great importance, since there were in Britain at that time two competing Christian traditions. The Celtic church had its origin in the Roman era and had established its own missionary tradition which had founded centres on the Continent, and which had a strong influence in the north of England. The other side is referred to as the Roman side since it had been established by the missionary work from Rome as ordered by Pope Gregory the Great. At Whitby, therefore, not only correct religious observance - itself an important issue - but also ecclesiastical power struggles were at play.

As an overview of this event and as a reminder of the importance of Easter, I will here quote from J. F. Webb's translation of Eddius Stephanus' Life of Wilfrid, published in The Age of Bede, Penguin Classics, 2004: 116-17. The account is found in chapter 10. Eddius' introductory information about Bishop Colman is largely incorrect (see Webb 2004: 116). It is also worth noting that this takes place before Wilfrid ascended to the episcopacy of York.

October, with Wilfrid on the far right

BL MS Royal 17 A XVI, almanac, England, c.1420

Courtesy of British Library

On a certain occasion while Colman was bishop of York and metropolitan archbishop, during the reign of Oswiu and Alhfrith, abbots, priests, and clerics of every rank gathered at Whitby Abbey in the presence of the most holy Abbess Hilda, the two kings and Bishop Colman and Agilberht, to discuss the proper time for celebrating Easter: whether the practice of the British, Scots, and the northern province of keeping it on the Sunday between the fourteenth and twenty-ssecond day of th moon was correct or whether they ought to give way to the Roman plan for fixing it for the Sunday between the fifteenth and twenty-first days of the moon. Bishop Colman, as was proper, was given the first chance to state his case. He spoke with complete confidence, as follows: 'Our fathers and theirs before them, clearly inspired by the Holy Spirit,as was Columba, stipulated that Easter Sunday should be celebrated on the fourteenth day of the moon if that day were a Sunday, following the example of St John the Evangelist "who leaned on the Lord's breast at supper", the disciple whom Jesus loved. He celebrated Easter on the fourteenth day of the moon, as did his disciples and Polycarp and his disciples, and as we do on their authority. Out of respect to our fathers we dare not change, nor do we have the least desire to do so. I have spoken for our party. Now let us hear your side of the question.'

Agilberht, the foreign prelate, and his priest Agatho bade St Wilfrid, priest and abbot, use his winning eloquence to express in his own words the case of the Roman Church and Apostolic See. His speech was, as usual, humble.

'This question has already been admirably treated by a gathering of our most holy and learned fathers, three hundred and eighteen strong, at Nicaea, a city in Bithynia. Among other things they decided upon a lunar cycle recurring every nineteen years. This cycle gives no room for celebrating Easter on the fourteenth day of the moon. This is the rule followed by the Apostolic See and by nearly the whole world. At the end of the decrees of the fathers of Nicaea come these words: "Let him who condemns any one of these decrees be anathema."'

These are Wilfrid's word on the subject, and the chapter continues with the king asking rhetorically the synod whose authority is the greatest, Columba or Peter the apostle. Since no one can deny the primacy of the prince of apostle, the case is settled and Colman is allowed to resign rather than having to enforce a break with his own tradition.

The Easter controversy was a matter of great contention, and we do well in treating Eddius' report with due skepticism. However, what we know for certain is that the Roman party won, and Wilfrid solidified his reputation as a learned man in these debates.

As a final note of explanation: Bishop Colman argues that they follow the tradition established by Saint John the Evangelist, and although both this and the Roman use of Saint Peter are questionable in historical weight, this highlights the importance of longevity, tradition and Biblical roots in church ritual. What is of particular interest to a saint-scholar like me is the reference to Polycarp (d.155). He was martyred in Smyrna and was believed to have been the disciple of John the Evangelist, hence his inclusion in Colman's argument of the chain of tradition. Aside from being a valuable insight to the rhetoric of the period, Colman's speech gives us also a glimpse of the standing of Saint Polycarp in seventh-century Britain.

Etiketter:

Books,

History,

Medieval,

Religion,

Saints,

Translations,

Whitby,

Wilfrid of York,

York

søndag 20. mars 2016

Edward the Confessor in Dringhouses

Ever since writing my MA thesis on

Edward the Confessor, I've had a minor obsession with all things

related to his posthumous cult. Regular readers of this blog will be

aware of this already, as might be attested to by the number of

blogposts touching on this particular subject (a list of which will

be added after the present post).

It was for this reason that I have been haunted by the idea to pay a visit to the Church of Saint Edward at Dringhouses, a village just outside York. Fortunately, while I was staying in York for two months as part of my PhD programme, I lived just about fifteen minutes away from the church and decided that it was high time I had a look around. Typical of my propensity for procrastination, I left it to the very last day I was in York, but luckily I did manage to get around it.

It was for this reason that I have been haunted by the idea to pay a visit to the Church of Saint Edward at Dringhouses, a village just outside York. Fortunately, while I was staying in York for two months as part of my PhD programme, I lived just about fifteen minutes away from the church and decided that it was high time I had a look around. Typical of my propensity for procrastination, I left it to the very last day I was in York, but luckily I did manage to get around it.

The belltower. The spire was replaced in 1970

This part is most likely the vestry, which was added in 1902

The inner doorway

The church of Edward the Confessor was

built between 1847 and 1849, and upon its completion it was dedicated

to Saint Edward. This was in fact a re-dedication, as the new church

replaced a church from 1725 which had been dedicated to Saint Helen,

which in turn had replaced a chapel dedicated to the same saint. This

chapel is mentioned in chantry certificates as early as in 1546 and

1548. The church was financed by the widow of the late Revd. Edward

Trafford Leigh, and in memory of her husband she had it dedicated to

his namesake saint. Saint Edward's became a parochial church in 1853

when Dringhouses parish was established from parts of the parishes of

Holy Trinity and St Mary Bishophill Senior.

Saint Edward's church was constructed in decorated Gothic by the architects Vickers and Hugill (or Hugall) of Pontefract. This is perhaps especially evident in the windows and the doorways with their pointed arches and the leaf-work masonry on their side columns. Although there are several details of such beautiful handicraft, the exterior of the building is not remarkably opulent. The interior of the church is somewhat more so, owing in particular to the many splendid windows of stained glass.

Saint Edward's church was constructed in decorated Gothic by the architects Vickers and Hugill (or Hugall) of Pontefract. This is perhaps especially evident in the windows and the doorways with their pointed arches and the leaf-work masonry on their side columns. Although there are several details of such beautiful handicraft, the exterior of the building is not remarkably opulent. The interior of the church is somewhat more so, owing in particular to the many splendid windows of stained glass.

Nave, towards the choir

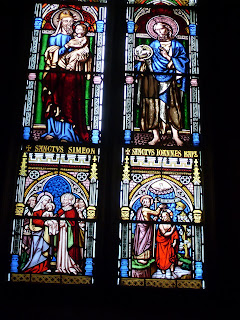

The oldest stained glass windows were

designed by William Wailes in 1849, and these depict figures and

scenes from the Bible. The first two windows below are found on the

left-hand side of the nave when facing the choir. The first window

depict the prophet Elijah (here Elias) with the scene showing him

being fed by ravens in the wilderness (1 Kings 17:4-6), and then

Moses with the scene showing the rod with the brass serpent (Numbers

21:4-9). The second window shows Saint Simeon holding the

Christ-child with a scene from the presentation of Christ in the

temple below (Luke 2:25-32), and then John the Baptist with the scene

showing the baptism of Christ in the River Jordan (Mark 1:1-8).

In the choir, the central window shows

the crucifixion of Christ with Mary and John the Evangelist at his

sides, with scenes from the Passion underneath. In the choir on the

left-hand side are Matthew and Marcus, while on the right-hand side

are Luke and John. Note especially how carefully John is made to be

identical with the depiction in the central east window.

On the right-hand side of the nave the

windows depict scenes from the New Testament. The first shows

parables of Christ, including the parable of the sower (Mark 3:4-9),

the parable of the lost sheep (Matthew 18:12-17), what seems to be

the parable of the talents (Matthew 25:14-30). The lower left panel

might depict Christ being rejected by a pharisee. The second window

shows Christ blessing the children (Matthew 19:14) with angels

underneath.

While the stained glass windows by

Wailes were very beautiful, I was chiefly interested in the sundry

depictions of Edward the Confessor himself, in order to see how his

iconography had been represented. The first depiction of Saint Edward

can be found in a niche above the doorway where a statue shows the

Confessor, bearded, wearing a crown and holding a ring and a sceptre

with a bird on its top.

This iconography is typical of the tradition of Saint Edward's cult. His appearance as a bearded monarch is attested already in the first biography, written relatively shortly after Edward's death in 1066, now referred to as Vita Ædwardi Regis. His white, and virginal, beard is made into evidence of holiness in the two twelfth-century hagiographies written about him, the first by Osbert of Clare in 1138 and the second by Aelred of Rievaulx in 1163.

The ring and the bird refer to two of the most iconical legends concerning the Confessor. The story of the ring can first be found in Aelred of Rievaulx's Vita Sancti Eadwardi, where it is told that the Confessor gave his ring to a beggar. This beggar turned out to be Saint John the Evangelist in disguise (the Confessor's particular saint), and Saint John, again in the disguise of a beggar, gave the ring to two English knights in the Holy Land, with the orders to take it to the king and report how they had received it. The ring remains the key iconographical feature of Saint Edward. (More on this here.)

The bird is a later feature, but it may have entered the iconography as early as the 13th century. By the end of the fourteenth century, the coat-of-arms of Edward the Confessor was held to be a golden cross on a blue background with golden birds in the open spaces between the cross arms, and one golden bird underneath the cross. We see this from Richard II's merging of his own coat-of-arms with that of Saint Edward.

In time there emerged a legend saying that Edward had once been disturbed by nightingales during prayer, and when he prayed that they should cease their singing for a while they did so. This legend appears to have an early modern date rather than belonging to the medieval tradition. (More on this here.)

Edward

the Confessor is also depicted inside the church. We see him on the

right-hand side of the altar, where he is flanking Christ in majesty

with Saint Peter standing on the left-hand side. The confessor is

here surrounded by four angels, two of which are carrying some of the

instruments of Christ's passion. Above Saint Edward's head we find

his coat-of-arms.

We

also find Saint Edward on the left-hand side of the bottom end of the

nave (when facing the altar). This is a stained glass window put up

in memory of churchwarden G. Raymond Burn who died in 1993. Here the

Confessor is shown wearing his regalia, but in a distinctly more

royal and notably less legendary form than in the other depictions.

The dedication of the church has also given name to at least one more place name in Dringhouses, namely St Edward's Close, as depicted below.

Websites:

http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/yorks/city-of-york/pp365-404

http://www.genuki.org.uk/big/eng/YKS/ARY/Dringhouses/Dringhouses90.html

https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1256466

For similar blogposts, see:

An overview of Edward's cult

Edward the Confessor and Thomas Becket

A wall-painting at Lyddington

Edward the Confessor and Kenelm of Mercia

Edward the Confessor and Saint George

The Wytham roundel

Edward the Confessor and Louis IX

Edward the Confessor's bloodless martyrdom

Edward the Confessor at Ickford

Edward the Confessor in Northern England

Edward the Confessor's feast-day

Edward the Confessor as King David

http://www.genuki.org.uk/big/eng/YKS/ARY/Dringhouses/Dringhouses90.html

https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1256466

For similar blogposts, see:

An overview of Edward's cult

Edward the Confessor and Thomas Becket

A wall-painting at Lyddington

Edward the Confessor and Kenelm of Mercia

Edward the Confessor and Saint George

The Wytham roundel

Edward the Confessor and Louis IX

Edward the Confessor's bloodless martyrdom

Edward the Confessor at Ickford

Edward the Confessor in Northern England

Edward the Confessor's feast-day

Edward the Confessor as King David

tirsdag 8. mars 2016

Three meditations on mortality

I find myself very fascinated with the different ways in which mankind approaches its own mortality. Reflections on death and transience are at the core of some of the most beautiful expressions of human culture, either in art, in writing, or in music. In the present blogpost I wish to present three items that share a common engagement with death, and which have caught my attention lately.

The first item belongs to music, namely Chopin's piano sonata no. 2 in B minor, opus 35, which is most commonly known as Marcha Fúnebre, Funeral March. This is a deeply iconic piece which I myself remember to have associated with death from a very early age, since it has been used in many forms of popular culture to denote death and mortality, to such a degree that merely to hum its theme has become a non-verbal shorthand for death and funerals.

Marcha Fúnebre, by Frédéric Chopin

The second item is from literature, and it is one I encountered for the first time only a few days ago. This is a brief poem by the Greek poet Constantine P. Cavafy (1863-1933), one of the major figures of modern Greek poetry. He lived most of his life in his native Alexandria, Egypt, with shorter residences abroad. The following poem is translated into English by Evangelos Sachperoglou and published in The Collected Poems, Oxford World Classics, 2007: 3-5.

Candles

The days to come are standing right before us,

like a row of little lighted candles -

golden, warm, and lively little candles.

The bygone days are left behind,

a dismal row of burned-out candles;

those that are nearest smoking still,

cold candles, melted and bent.

*

I don't want to see them; their sight saddens me,

and it saddens me to recall their former glow.

I look ahead at my still lighted candles.

I don't want to turn around, lest I see and shudder

how fast the darksome line grows longer,

how fast the burned-out candles multiply.

And with these last two heavy lines still echoing in the mind, I present the third and final item, this one from art, namely the death-mask of Cavafy himself, made in 1933 by an unknown artist and currently placed in the house-museum of Cavafy in Alexandria.

For similar blogposts, see:

Dance macabre

Et in Arcadia ego

Vanity of vanities

Abonner på:

Innlegg (Atom)