if you want to dream, keep those dreams massively achievable

- Richard Ayoade, 8 out of 10 cats does countdown S20E03

In

my previous blogpost, the last of 2021, I provided an overview of some

highlights from my reading that year. These highlights constituted more than

the individual books themselves, as part of what made them highlights had to do

with aspects related to but extraneous from the act of reading itself. One such

aspect is rooted in one of the cornerstones in how my reading through any year

is selected and decided, namely the multiple lists that I aim to cross out

every year. I briefly alluded to these lists in my previous blogpost, and

thanks to a very positive response from friends I have decided that the first

blogpost of the new year will be a presentation of these lists and why I employ

them as guidelines.

Why lists?

Before getting into the lists themselves, however, it is perhaps relevant to

note that a fundamental rationale behind my extensive use of lists has to do

with my personality and its constellation of virtues and vices. On the plus

side – I believe – I am a voracious and very curious reader, who will happily

yet not indiscriminately venture into unknown literary fields. On the negative

side, however, I am also a very slow reader, and the combination of my personal

slowness with the general finiteness of human existence means that I am forced

to make choices in my readings. After all, no one goes into a library and work

their way through it from A to Z (or A to Å in Norwegian).

In addition to this more existential constraint, there are also two aspects

that have an impact in my reading through any given year. On the one hand,

there is the issue of my work requiring a lot of reading, which in turn affects

how I choose my books. On the other hand, there is a part of me that easily

tires of routine and constraint, and which therefore is prone to embark on a

book simply because I want to read it. Since I am also driven by

professionalism and frivolity – in addition to my concerns regarding finiteness

– I am using more than one list simply for the sake of variation. My greatest

fear as a reader is to get stuck and to tire of reading altogether.

The lists

My first reading list was compiled in the spring of 2008. It was my first year

at university, and I was increasingly taking in the vast literary world to

which I had access. Trips to the campus bookshop and the library were

exhilarating excursions that left a deep imprint on me, but at times also

simply overwhelmed me. It was in this period of careful forays into the wider

world of literature that I wrote down two lists: One of books I had read, and

one of books which I would like to read. The second one consisted of a

relatively diverse array of well-known and lesser-known books, mainly fiction,

yet this diversity was severely hampered by my general inexperience of the literary

world’s infinite possibilities. Even so, the list was a product of my

continuing desire to eventually be well-read, interesting and cultured, and I

although I have removed some items from the list as they have fallen out of

interest, I continue to believe that if I do manage to get through all these

books, I will be much better for it.

As I had compiled the second list, I quickly saw that this was going to be a

life-long project, yet despite this revelation – or perhaps perversely because

of it – I turned my attention to other titles instead. It was only in the

course of 2009, if memory serves, that I started to let this list guide me more

systematically. It was also then, I think, that I stopped putting new items on

that list, even though the number of books that I wanted to read grew steadily

for each new course I took.

Several years later, as my list of books that I had read grew longer, and my

list of books I wanted to read did not diminish as quickly as I had hoped, I

was introduced to another system of lists thanks to my youngest sister. This

system was comprised of triads: Three books in three or more categories that

would guide the reading in the course of a year, and that would open up for

some variety. As my desire for titles had gone way beyond the list from 2008 at

that point, possibly in 2013, I embraced this system and set down four

categories from which to choose my titles. I still use these categories to this

very day.

One category is my reading list from 2008. Even though I have picked up the

pace, there are still, at the time of writing, 138 books to be crossed off,

some of which are quite lengthy. For this reason, making sure that I at least

go through a minimum of three each year will hopefully keep inspiring me to

finish before I reach the age of 80.

A second category consists of Nobel laureates in literature. This category is

more of a mixed bag in my eyes. Whereas my list of 2008, at least in its

current configuration, solely includes items that I think will either extend my

literary horizon or at least fill in various embarrassing gaps, the selection

of Nobel laureates is beyond my control and sometimes contrary to what I

consider to be necessary reading. For instance, in 2016 I read Harold Pinter’s The

Homecoming and disliked every second of it. Granted, there is value in

having read it, and there are very few books that I will consider unworthy of

reading, or that I will regret reading. But I think it is fair to say that I

would not have finished The Homecoming had it not been for Pinter’s

status as a Nobel laureate and the canonicity conferred upon him by that status.

For this reason, I do not prioritise the Nobel list as highly as I do others.

A third category is Norwegian books. As I had spent much of my early twenties

reading anglophone literature, I came to the realisation that I had neglected

the literary heritage of my native country, which is both rich and interesting.

In a move to rectify my ignorance and inexperience, I decided to read a minimum

of three books that can in some way or another be construed as Norwegian. This

means that I do not limit myself to books written by Norwegian authors since

the country’s established autonomy in 1814, or its independence in 1905, but in

general books that have been produced within, or by people from, the cultural

geography known as Norway at any given point in time.

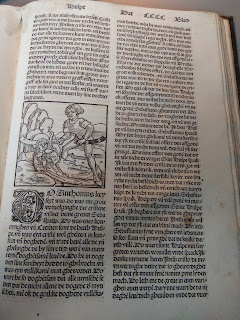

A fourth category is academic books. This category comes in part from the

acknowledgement that my professional life presides over much of my reading in

the course of a year, but rarely in the form of entire books. Very often, I

will consume academic literature in the form of articles, perhaps chapters, and

often in a rather squirrelsome way, meaning that I am looking for specific

pieces of information from which I can build my own texts, my own arguments, or

my own teaching. This category is a way to ensure that I also read some books

in full.

In addition to these two categories, there are two others that I eventually

realised were necessary in order to make even more of my reading. The first of

these two categories is books by women. Because I am a medievalist, a lot of my

source material and a lot of the older academic texts that I still need to

consult are written by men. Moreover, since many of the books I included in my

list of 2008 are drawn from the Western cultural canon of before 1900, there is

an overweight of male writers. Similarly, the list of Nobel laureates is

heavily male-dominated, and continues to be so. I am, however, deeply convinced

that a wide reading serves the purpose of gaining a wider understanding of the

world and its reality, and for that understanding to be attained it is

necessary to read a wide representation of humanity. One way of ensuring a wide

representation is to consciously read more women, and that includes, of course,

trans women. Additionally, and perhaps especially in relation to the next

category, I have found that many female authors have access to or are conscious

of social issues and spheres that many male authors have historically either

neglected or badly misrepresented. Consequently, I find myself benefitting

greatly from reading books by women – beyond the quality of the individual

books.

The final category came into place in the autumn of 2017, and I have written

about it on this blog at various times already. This category is to read one

book from each of the world’s 197 countries (and also Western Sahara, which is

not yet recognised by the UN). My project of travelling the world by page was

inspired by the project A Year of Reading the World by British journalist Ann

Morgan, and I picked it up after I had handed in my PhD thesis. So far, I have

had a great range of experiences, and learned much more than I had anticipated

– naturally – and it continues to be a project that pays enormous dividends. In

combination with the previous category, reading women, I often seek out works

by women from the new countries, and this, I believe, has provided an even more

nuanced view of various countries of their cultures than I would otherwise have

had.

These six categories, then, are what guide my yearly reading. Often, they can

be done in combination, fortunately, but in any case, they ensure that I do not

tire of reading anytime soon. In addition to these categories, of course, I

also pick up books that do not belong in any of them, breaking free of the

guidelines and the lists completely. I have so far avoided calling this a

seventh “sundries” category, although in effect that is exactly what it

is.

The lists in 2021

As much as I enjoy talking about books and reading, I have long been very

hesitant to enumerate things I have read. Such enumerations – or lists of

finished reading, rather – often have or can be seen as having a competitive

undertone. Personally, I am very fond of such overviews, because they often

provide great recommendations. However, since reading is about quantity rather

than quality, and since we all have different frameworks that open up or limit

our reading, I will close this blogpost with one book from each of the six

categories by which I have organised my reading in the previous year. All in

all, 2021 was a very good year for reading, and I hope that 2022 will prove

even better.

Category 1, a book from my old reading list: Christopher Marlowe, Doctor

Faustus

Category 2, a Nobel lauerate: Louise Glück, The Wild Iris

Category 3, a Norwegian book: Helge Ingstad, Klondyke Bill

Category 4, an academic book: Henry Bainton, History and the written word

Category 5, a book by a woman: Elizabeth Lambourn, Abraham’s luggage

Category 6, a book from a new country: Maïssa Bey, Do you hear in the

mountains (Algeria; translated by Erin Lamm)

Following these categories, I am pleased to say that I did manage to read more than the minimum requirement of eighteen different books, and so the system – in its crooked way – definitely works for me. I hope it will continue to do so in the coming months.