In May, I spent a few days in Santiago de Compostela, a city rich in history and a place important to my own academic interests. In future blogposts, I hope to share several details from the Compostela's multilayered past, and I am collecting these posts under the header 'Cantigas de Compostela', an admittedly clumsy alliterative pun on the famous thirteenth-century collections of songs known as the Cantigas de Santa Maria.

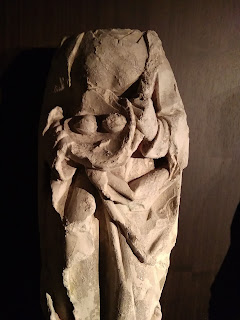

The first instalment in this new series is a reflection on a type of mystery specific to the scholarship on the cult of saints. As I was exploring the impressive museum of the cathedral of Santiago de Compostela, I noticed a headless statue carrying two items in a bowl. According to the sign in the museum, the statue is one among several that once decorated one of the cathedral's chapels, and it was made in the middle of the sixteenth century, possibly in a Flemish workshop, or by Flemish masons working in Spain.

The statue has been identified as Saint Lucy, a virgin martyr from Sicily who was believed to have been killed during the Diocletian persecutions of the early fourth century. Her cult was revivified following the publication of Legenda Aurea written by Jacobus de Voragine in the 1260s, and she features in many works of late-medieval art. At the time of writing, I do not know whether the identification of this statue rests on any information outside what the statue itself provides. For instance, whether there are archival material referencing these statues, earlier descriptions of the chapel from when the head was still attached, surviving fragments, or any other indicators that point in this specific directions. If we consider the statue itself, however, things are less clear.

The best argument for Lucy as the saint in question is the the bowl containing two items. According to legend, Lucy was blinded, and her eyes became her defining attribute in art, often shown as presented on a plate or a bowl, as in the case of this statue. However, there is also another candidate, namely Saint Stephen, who was stoned to death according to the account given in Acts, and his main attribute in late-medieval art is a selection of stones. The display of these stones can differ according to the medium or the choice of the artists. In statues, the stones are typically held, whereas in paintings or frescoes the stones can be placed elsewhere, as in the case of Carlo Crivelli's rendition, where the stones are balanced on the saint's head and shoulders. In short, we have two saints who are known by their presentation of round or roundish items, and this is all we have to go on in the case of the statue in the cathedral museum. (The clothes do not yield any clues, as without the original paint, which might have included patterns that could have pointed to a specific gender or social position, they are too generic to allow for any conclusions.)

What about the items themselves? This is, perhaps, the only clue to which we can reasonably cling. Although we should be mindful of the choices of individual artists, or at least different traditions of individual workshops, the number of items is significant. Naturally, Lucy is typically depicted with both her eyes on a plate - even though she is also typically depicted with her eyes in their original place at the same time, because she is a saint and therefore posthumously healed. The stones of Saint Stephen, on the other hand, ordinarily come in slightly higher numbers, either as a pile whose total number is only hinted at by the stones on the top and at the front of the pile, or as three or four held in the saint's hands. While it is possible that an artist or a workshop would depict only two of Saint Stephen's stones, the number does suggest that Lucy might be the correct identification.

Ultimately, however, we do not know, but the case does serve as a good reminder of how crucial iconography is to the navigation of medieval art, and how sometimes the attribute of a saint might be the only thing that allows us to pinpoint the saint's identity.

On Englands pleasant pastures seen!

- And did those feet, William Blake

søndag 30. juni 2024

Cantigas de Compostela, part 1: Saint Stephen or Saint Lucy?

lørdag 29. juni 2024

Histories from home, part 4 - an object lesson in wishful thinking

Yesterday, I went for a hike in an uninhabited and uninhabitable valley close to the family farm in my native village of Hyen in the Western Norwegian fjords. As far as we know, the valley - named Skordalen, or Cleft Valley - has never been settled by humans, and the main reason for this is the harsh winters that make it very difficult to travel in and out of the valley. Yet as most parts of my native village, this valley has been used by generations of farmers to collect fodder for the animals and food for themselves. Several generations ago, it was common to build various storage buildings throughout the non-arable parts of the village. In these buildings, fodder or turf was placed after it had been gathered, and in the winter, when the snow allowed for easier transport using sleds, the hay or the turf would be brought back to the farm. Each building had its particular use, and so a hay barn was placed in a different place, and also built differently, than a turf house. (Turf was used either for the roof or crumbled up and placed beneath the livestock in the byres to soak up the piss and shit, and to make them have a softer surface on which to lie.)

Throughout my upbringing, my family has encountered the stone foundations of several such outdoor barns. These stones are all that is left, and can be sometimes difficult to recognise in a terrain already dotted with rocks that have either been left by the ice or a rockslide. Whenever I go hiking in this valley, I always keep a look out for traces that could point to a now-lost outdoor barn. Yesterday, I thought I found one - or rather, I thought I found two - but I also know from experience that I have been wrong about such assessments before. The case about which I am most convinced is pictured below, and I will eventually have to return in order to assess whether these stones are likely to have been moved about and placed against one another by human hands, or whether it is merely a matter of nature running its course. What always makes this a difficult question, is that the farmers would have used stones that were already lying close together, and so the subsequent natural processes will easily shift the stones to such a degree that they look as if they are naturally placed. In this particular case, as pictured below, further studies are required.

fredag 21. juni 2024

New publication: Legitimizing Episcopal Power in Twelfth-Century Denmark through the Cult of Saints

In my previous blogpost, I announced the publication of a new volume of academic articles, of which I am one of the co-editors. Information about the volume, its content and its general argument can be found here, while the open access edition of the book can be found here.

Aside from being one of the co-editors, I also contributed with a chapter of my own, titled 'Legitimizing Episcopal Power in Twelfth-Century Denmark through the Cult of Saints', which can be downloaded here. The article is an examination of how the bishops of Odense, Ribe and Lund used the cults of Saint Knud Rex, Liufdag, and Thomas of Canterbury respectively, in order to strengthen their legitimacy vis-à-vis other elite groups of twelfth-century Danish society. The article brought together a number of my academic interests - chiefly the cult of saints, the construction of identity, and Danish history - and was great fun to write, as it allowed me to pursue some old topics and explore some new ones as well.

This blogpost is prompted by my trip to the post office in my village in the Norwegian fjords, where I picked up my author/editor copy of the book today, and could finally get a physical sense of the labour that took three years to complete.

lørdag 15. juni 2024

New publications: The Cult of Saints and Legitimization of Elite Power in East Central and Northern Europe up to 1300

In 2021, I was hired as a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Oslo, working as part of a project that was a collaboration between the University of Oslo and the University of Warsaw. One of my tasks in this period has been to co-edit a volume of articles together with Grzegoz Pac and Jon Vidar Sigurdsson, based on a conference we co-organized in Warsaw in the autumn of 2021. The volume collects a number of articles that explores how various elites in East Central and Northern Europe. The scope of the volume, and the comparative aim, served as a backdrop for the core purpose of the project itself, which was to explore the way elites in medieval Norway and medieval Poland sought to legitimise their positions in society. The volume includes case studies from both Norway and Poland, but also from several other countries.

The process has been immensely educational, and, although often tiring and frustrating given the nature of such editorial endeavours where there are so many details to keep in mind, a phenomenal opportunity for seeing how much interesting and novel research is being undertaken in our section of academia. Seeing this book published is both a relief and a joy at the same time.

A description of the book can be found on Brepols' website, and the book itself is freely available in open access. Each individual article can be found here.

There are numerous reasons why I am deeply satisfied with this book, and very proud of it. One of these reasons is the introduction - to be read here - which provides both a broad historical context for the cult of saints, and a discussion of the various forms of legitimisation to which the saints were used in the newly-Christianised polities of Northern and East Central Europe.

I also contributed with a chapter of my own, but this is the subject for a future blogpost.