I

am an indifferent diarist, both because I lack the required stamina and because

my life is not sufficiently interesting to warrant much page-space. There are,

however, some ways by which I record the vicissitudes of the years, and one

such way is by keeping track of my reading. Both as a scholar and as a private

individual, much of my time is taken up by reading and also, to a lesser extent

by writing, and when I am doing neither I am very often thinking about what I

should be reading or what I should be writing. In essence, my life revolves

around texts, as is the case of so many others of my various friends and

colleagues.

My reading through a calendar year is guided by various lists. These are goalposts

I have set myself, and that have guided my reading for years – the first of these

lists came into place in 2008, and since then new lists have emerged. In

another blogpost, I might go into greater detail about this reading by lists,

as it is a key aspect of how I choose my books and how my reading comes

together in the course of a year. For the current blogpost, however, I merely

mention this as an explanation of the seemingly sprawling nature of my literary

choices, as I take the opportunity of the closing year to reflect on some of my

highlights from a year of reading.

Travelling by page

Given the pandemic, as well as constrictions owing to money and work, my travelling

this year has been rather limited. However, one way of creating some balance in

an otherwise rather stationary daily life is to travel by page, and throughout

the year I have visited several countries in this way. Some of these countries

I have visited for the first time, such as the Marshall Islands, Qatar, Guinea

Bissau and Libya. In other cases, the travels have been either revisits or

parts of a longer travelogue from a time when the political map was very

different from what it is now, meaning that the current names have little meaning

when outlining the journeys. Examples of such books are the travelogues of Benjamin

of Tudela and Odoric of Pordenone.

Improving languages

Reading is not only done for the purposes of vicarious travel, but also for maintaining my linguistic skills. This element is part of every kind of reading I do, no matter whether the text is in my native Norwegian or another language. This year, I have dedicated some time to improving my Spanish, a language I love dearly and which I should know more fluently than I currently do. Throughout the year, therefore, I have kept returning to various books in the Spanish language – books at various levels, ranging from the comic Mortadelo y Filemón by Francisco Ibáñez to the more complex baroque prose of Jorge Luis Borges or the poetic scenes of Raquel Lanseros and Maribel Llamero, two of my favourite poets in any language. Especially the books of poetry have been of great use in this endeavour, as I have brought them with me on various hikes and journeys, and in this way also used them to connect more strongly with my own native land – but this connection, however, is material for another blogpost

New places for reading

One important and pleasurable aspect of a reading life is to find new places in which to read, new vantage points from which to see the world, and, very often, new scenes that can provide contrasts between what is being read and where it is being read. For the first eight months of 2021, I was in one way quite constrained in my options for new places for reading, since I was staying in my native village in the Norwegian fjords where I grew up. However, even though the village itself is very small, the area throughout which the village is sprawled is quite vast and full of various nooks, crannies and overlooked places. Additionally, although I was staying in my late grandparents’ house, a house where I spent a large part of my childhood, this year I started using some new spaces in the house for work – and work usually entails at least a modicum of reading. So it was that from January through August, I installed myself in a temporary office indoors, then, when the temperatures permitted, I moved to the porch. Moreover, I spent several wonderful afternoons paddling along the shores of the lake behind the house, deliberately seeking out new spots for reading, and I found a few that served excellently well. These were places that I knew about, but which I had typically passed by when traversing the lake, be it on ice or by canoe, but upon closer inspection they proved to be ideal reading spots as well.

The opportunities for finding new places for reading opened up even further when I started a new job in Oslo in September. Despite pandemic restrictions and a general caution on my part, I found that the library café of the humanities campus of the University of Oslo provided a splendid vista for early morning reading on the way to the office, or as a workspace for writing notes for articles.

I also sought out new haunts in the city centre, and I was enchanted by the café Kaffistova (literally, the coffee room), which used to be a meeting place for students and academics from Western Norway about a century ago. While it is now a popular spot for a much wider clientele, there is something of the romantic in me that takes pleasure in reading in a place where other Western Norwegians in academic exiles gathered for a bit to eat and, presumably, to feel a little closer to home. In this place, I have so far mostly read classics from the Oslo literature – books that are set in Oslo and that provide very fascinating details to the city as it was in a bygone age. The first of these was Bondestudentar (Farmer Students) by Arne Garborg, (1851-1924 who also was a Western Norwegian studying and working in Oslo.

Another aspect of finding new places is that these places open up for new contrasts between the reading and the place of reading. This aspect also ties in with travelling by page, and since I have mostly done my reading in Norway this year – and exclusively in the northern half of Europe – there can sometimes be quite notable contrasts between where my body is located and where my mind is wandering, guided by the words penned by authors from other parts of the world. So it was that in the Norwegian urban autumn of Central Oslo I read short stories from Morocco by Leila Abouzeid, and while the first significant snowfall still covered the pavements, I read Norbert Zongo’s dictator novel The Parachute Drop, set in the sweltering heat of a fictional West African republic.

Sundry highlights

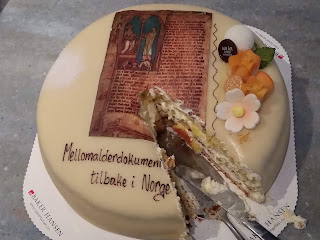

In addition to these three categories, there were also other highlights that are not as easily categorised, but which nonetheless were key points in making my reading year both memorable and pleasurable. For instance, my family and I visited the Norwegian book town (Den norske bokbyen) in the village of Fjærland, a couple of fjords to the south of my own native village. It is always a joy to wander among the numerous book stalls and shops surrounded by a spectacular scenery, and it was great to be back for the first time in several years. Another, and very unexpected highlight, came when I attended a seminar organised by colleagues in Oslo, where they were celebrating that the thirteenth-century manuscript Codex Hardenbergianus containing the law code of King Magnus Lagabøte (r.1263-80), the Law-mender, had been returned to Norway from Denmark. For the occasion they had commissioned a cake containing a picture of the first folio of the manuscript, and I was fortunate enough to have a slice of it.

Other highlights came during a trip to Odense, where I had been invited to speak at a workshop on medieval manuscript fragments. This allowed me to visit a city that is one of my homes away from home, and where I had not been since the autumn of 2019. I sought out one of my favourite cafés and sat down with a cup of tea and Albert Memmi’s The Colonizer and the Colonized while enjoying the familiar scenery and the familiar sounds. The workshop also brought me back to the researcher’s reading room at the University Library of Southern Denmark, where I spent much of 2018 and the spring of 2019 researching the fragments of the university library’s special collections. It was also there that I gave my presentation, addressing several of the fragments that a friend and colleague and brought out for the occasion. The workshop culminated with my first trip to the National Archives in Copenhagen, where we were shown some of the many treasures kept there.

One of the final highlights of the year came when I returned home for Christmas, and was met with an author’s copy of a journal issue to which I had contributed. The text itself was written in 2015, so it is not new as such, but back then it was only published digitally, so it was a great pleasure to see it in the paper.

There were several other memorable moments of reading this year, moments that remind me how much I gain from reading in the way I do, and moments that inspire me to press onward and explore new literary horizons in the coming years. I am already excited about what reading I have ahead of me in 2022, and while I know some of the titles to add to my list of read books – the closest I’ll come to a diary, I suspect – there are others that are as of yet unknown to me.

Similar blogposts

For other blogposts touching on my encounters with books in 2021, please see the following.

The joy of aimless reading, on reading without a particular purpose beyond learning.

Remembered readings, on recalling circumstances from past encounters with books.

Travelling by page, elaborating a little on this aspect mentioned in the present blogpost.

A return to the roots, on going back to a book once frequently used.

Read at the right time, a reflection on the feeling of immersing oneself in a book at a serendipitous point in time.

Back to the old haunt, a reflection on the fragment workshop in Odense.