That iolly shepheard, which there piped, was

Poore Colin Clout (who knowes not Colin Clout?)

He pypt apace, whilest they him daunst about.

Pype iolly shepheard, pype thou now apace

Vnto thy loue, that made thee low to lout;

Thy Loue is present there with thee in place,

Thy Loue is there aduaunst to be another Grace.

- The Faerie Queene, Edmund Spenser

How many thousands never heard the name

Of Sidney, or of Spenser, or their books?

How many thousands never heard the name

Of Sidney, or of Spenser, or their books?

- Musophilus, Samuel Daniel

(...) our sage and serious poet Spenser, whom I dare be known to think a better teacher than Scotus or Aquinas

- Areopagitica, John Milton

- Areopagitica, John Milton

Lo I the man, whose Muse whilome did maske,

As time her taught, in lowly Shepheards weeds,

Am now enforst a far vnfitter taske,

For trumpets sterne to chaunge mine Oaten reeds,

And sing of Knights and Ladies gentle deeds;

Whose prayses hauing slept in silence long,

Me, all too meane, the sacred Muse areeds

To blazon broad emongst her learned throng:

Fierce warres and faithfull loues shall moralize my song.

- The Faerie Queene, Edmund Spenser

I once scornfully remarked that John Keats was essentially an over-emotional fanboy, after having read his sonnet On sitting down to read King Lear once again. Unfortunately this remark has rendered me a hypocrite, for since then it has become obvious to me that I am myself an equally passionate fanboy, although instead of Shakespeare I direct my adoration to Edmund Spenser. For those of you who know me well or have read some of my blogpost this should not come as a great surprise, Spenser being the most frequently quoted poet on this site. However, since I harbour such great admiration for his poetic genious I decided to make a pilgrimage to his grave in Westminster Abbey as a part of my trip to London.

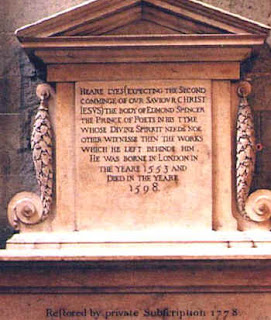

In his bridal song Prothalamion Edmund Spenser refers to London as his "most kindly nurse, / That to me gave this life's first native source", and as events unfolded it was also to become his grave. Spenser died in 1599 having fled his home in Kilcolman, Ireland, after the Tyrone rebellion, penniless according to Ben Jonson, and certainly profoundly shaken emotionally. He was buried next to his own hero Geoffrey Chaucer and his coffin was attended by poets who placed upon it elegies written in his honour. The exact whereabouts of his grave is unknown and when an excavation was carried out in the 19th century to save the elegies, the search was fruitless - something it would have been, presumably, even if they had managed to locate his grave.

Mr. Beeston sayes he [Edmund Spenser] was a little man, wore short haire, little band and little cuffs.

- Brief Lives, John Aubrey

Picture of Spenser's tomb is taken from www.poetsgraves.co.uk.

I had greatly looked forward to this little pilgrimage and to pay the proper respects to my poetic idol, the prince of poets and, in my opinion, the true English bard. However, the pilgrimage was somewhat disappointing, partly due to the fact that Westminster Abbey is littered with tourists (something I do not cope with very well, I confess), partly because there was some restoration work going on in a neighbouring chapel and partly because Poets' Corner, for all its fame, does not exude or elicit reverence since the graves and memorials are all heaped together. Nonetheless I took out an old volume of Spenser's collected poetical works and read to myself the stanzas from Book VI of The Faerie Queene where Spenser's persona Colin Clout breaks his pipe. Thomas Roche, editor of the Penguin edition of The Faerie Queene, considers this to be Edmund Spenser's public, yet highly allegorical, withdrawal from poetry, akin to how critics have perceived Prospero's submerging of his books in Shakespeare's The Tempest.

Originally I had toyed with the idea of following the example of poets past and write my own elegy to the Prince of Poets at his grave. Unfortunately the location and its surroundings do not invite to lofty elegiac thoughts, so I disconnected the creative part of my brain for a while and strolled about in the Abbey more as a tourist than scholar or poet.

Although I failed to compose an elegy in Westminster Abbey, I had written a sonnet in Spenser's honour long prior to my arrival in England. I was hoping, this time, to produce a better poem, a more elegiac poem, but since this did not happen I will now present my work in honour of Britain's greatest poet. The sonnet is written in the Spenserian stanza and was completed almost a month after I had finished reading The Faerie Queene. It may appear strange during the first reading, but this is probably due to my imitation of the Spenserian spelling - an antiquated rendition of his contemporary language, attempting to bring it closer to the Middle English of Chaucer's time, that caused Ben Jonson to say, tongue-in-cheek, that "Spenser writ no language". The sonnet shows first of all poetic immaturity and a Keatsian fanboyism, but I hope there is sufficient intertextuality to find it an amusing read.

In Praise of the Unlearned Weaver

When I behold your craftfull tapestry,

I gin to doubt if fairest Philomel

Could with her work match your sweet industry

Or with her thread a greater story tell;

But pierlesse art is ne'er rewarded well,

But pierlesse art is ne'er rewarded well,

And solace oft denied a poet's pains;

Such spiteful fate your labours hard befell.

Your mastry poesie does entertain,

And also seeks the virtues to engrain

Fast to the fabric of the reader's mind;

Such spiteful fate your labours hard befell.

Your mastry poesie does entertain,

And also seeks the virtues to engrain

Fast to the fabric of the reader's mind;

And those who sought to make your struggles vain

Were to your dext'rous nature deaf and blind.

As shown by your delightful sonnetry

As shown by your delightful sonnetry

You can both weaver and a shepherd be.

- December 2009 – March 18 2010

- December 2009 – March 18 2010

Notes

Title: The title and weaving imagery of the poem draws on Spenser's own words in a dedicatory sonnnet to Lord Grey of Wilton, prefaced to The Faerie Queene, in which Spenser claims his rhymes to have been "wrought in an vnlearned Loome". It also points to the Spenserian sonnet structure, which through its rhyme scheme weaves the sonnet together in a way I find very pleasing.

Craftfull: This neologism plays on Spenser's own neologism "tradefull" which he employs in sonnet 15 of Amoretti, his sonnet cycle dedicated to his bride Elizabeth Boyle.The meaning is that Spenser's verse is very well crafted with its frequent puns and neologisms.

Philomel: Philomela is a figure of Greek mythology, a princess of Athens who was raped by her brother-in-law Tereus. To hide his transgression Tereus cut off Philomela's tongue, but she revealed the injury wrought on her by weaving a tapestry depicting the story. After her sister had avenged her, Philomela was turned into a swallow. Her metamorphosis is often confused with that of her sister Procne, who was transformed into a nightingale. I considered it a fitting comparison with Spenser as a weaver, since Philomela is the most famous storyteller of that medium in Western legendary tradition.

But pierlesse art is ne'er rewarded well: Despite being considered the prince of poets in his own age, Spenser has in later times taken a backseat to a number of poets and is no longer as well-known or widely read as might be expected. This fate was already pointed out in Jacobean times by Samuel Daniel, as quoted above, even though The Faerie Queene was printed in a complete edition in 1611.

And also seeks the virtues to engrain: Spenser, an Elizabethan Protestant and fierce anti-Catholic, wrote The Faerie Queene partly as an allegory of chivalry and its Christian values. Each of the books is dedicated to a particular virtue which also is represented by the protagonists. The first book has as its protagonist the Knight of the Red Cross who embodies holiness, although this holiness is achieved or repossessed only after he has purified himself from sins committed throughout the book in a pilgrim's progress of allegorical beauty. It is therefore no wonder to understand John Milton's sentiment with regards to Spenser as a teacher of good morals. Spenser had originally planned to write one book for each of the 12 traditional virtues, as he wrote to Walter Raleigh in a letter from 1589, but sadly this was never to be fulfilled.

And also seeks the virtues to engrain: Spenser, an Elizabethan Protestant and fierce anti-Catholic, wrote The Faerie Queene partly as an allegory of chivalry and its Christian values. Each of the books is dedicated to a particular virtue which also is represented by the protagonists. The first book has as its protagonist the Knight of the Red Cross who embodies holiness, although this holiness is achieved or repossessed only after he has purified himself from sins committed throughout the book in a pilgrim's progress of allegorical beauty. It is therefore no wonder to understand John Milton's sentiment with regards to Spenser as a teacher of good morals. Spenser had originally planned to write one book for each of the 12 traditional virtues, as he wrote to Walter Raleigh in a letter from 1589, but sadly this was never to be fulfilled.

And those who sought to make your struggles vain: One reason for Spenser's decline in popularity can be ascribed to literary critics of later ages. Samuel Johnson, for instance, disapproved of his archaic language, and early 20th century critics, like Eliot, if I remember correctly, were rather dismissive of his work.

Sonnetry: This is another neologism, but after coining it I discovered that it had already been coined.

You can both weauer and a shepherd be: Spenser's first poetic publication was The Shepheardes Calender, a series of 12 eclogues in emulation of Vergilius, another hero of Spenser's. In this array of highly experimental poetry Edmund Spenser created the persona Colin Clout for himself, named after a poem by John Skelton. Whereas Vergilius masked himself as Tityrus in his Eclogues, Spenser appears as the dejected shepherd Colin Clout who also, as indicated by the first epigraph, makes an appearance in The Faerie Queene.

Poore Colin Clout (who knowes not Colin Clout?)

The illustration to the first eclogue is taken from www.luminarium.org. Notice the broken bagpipe, an image Spenser would return to in his great epic.

Ingen kommentarer:

Legg inn en kommentar