Uses of the Middle Ages in a modern context are a bit like dust bunnies: Once you start looking for them, they are everywhere, sometimes even in rather surprising locations, or in unexpected forms and shapes. One frequently recurring form of medievalism is the use of the Middle Ages as an origin point for modern commercial products, where a modern manufacturer will employ references to the medieval period as a way to sell their merchandise, creating the illusion of a link with ancestral practices. The reference points depend on the culture in which the merchandise is peddled. Knights, monks, saints, Vikings, crusaders, kings, queens, nuns and jesters are some of the typical figure that are employed either separately or together, serving ultimately to persuade the buyer that by choosing this particular product, they will connect to a heritage that extends centuries into the past. Such strategies can yield amusing or funny results, but they can also be quite insidious given the right political context.

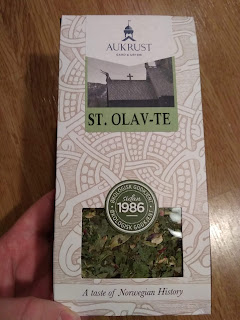

One such example of a product that relies on the buyer's fascination with the Middle Ages is a range of herbal teas that I have encountered both in the fjords back home, as well as in the Museum of Cultural History in Oslo, where the above picture was taken. The herbal teas are named after two of the most important Norwegian saints, SS Sunniva and Olaf. So far I have not been able to find a tea named after the third main Norwegian saint, Hallvard.

Products that rely so clearly on the medieval past to sell their product often find different ways to do so, but a common strategy is to provide a bit of explanatory text, whereby the link is forged a bit more clearly. In the case of the St. Olav tea, this link is forged by reference to two typical but in a way disparate elements from the Norwegian Middle Ages. The herbs are said to be well-known staples of monastic herb gardens, and the selection includes angelica, which is here claimed to be a Nordic contribution to those herb gardens. This claim is notable since it emphasises Nordic participation in the development of medieval monastic culture, and in a way can be said to present Norway as an active part on the medieval stage. The connection between the tea and medieval monastic practices is also strengthened by the patterns and the logo of the brand, which are taken from the stave church in Lom. Although a stave church was a parish church and not connected to a monastic establishment, the evocation of one religious foundation helps bring the mind towards another type of religious foundation.

Interestingly, the manufacturer has not only employed the image of the idyllic cloister garden, but also combined this with references to Vikings. In the presentation of the product, the manufacturer states that Vikings used wild-growing herbs, and then going on to provide an estimate of the number of stave churches that were erected after Norway's Christianisation. This joining of two disparate types of imagery - warriors and the institutions they sacked - is at first confusing, but can also be said to make perfect sense from a marketing point of view: All bases are addressed, both those who are drawn to the quiet romanticism of monastic life, and those who aspire to be manly men like the Vikings. The link to the Vikings are also alluded to in the opening text of the content description, where the tea is described as a tea for peaceful times between the battles. Now, the expression "between the battles" is very typical in Norwegian, and simply means between busy periods. In a context that plays on a connection with Vikings, and for a product that is named after a Viking-turned-Christianising-king-turned-saint, the expression does take on a slightly more literal meaning.

The marketing strategy in this case fascinates me, as it is a typical yet very convoluted and layered employment of Norway's medieval past in order to sell tea, a product that was not known or used in medieval Norway. In this way, there is both an element of achronology - Norway's pre-Christian and Christian past evoked in the same breath - but also of anachronism, since the product that is supposed to embody these links to the past was not used in the past to which it is being connected. I find this interesting because I believe the strategy says a lot about us modern people, not only the manufacturer, but also those who buy the product. And after all, even though I have bought this tea for the sake of a scholarly point, I have spent just as much money on it as someone who buys it in order to be more like a monk, or a Viking, or like Saint Olaf. So it is clear that advertisements work.

Ingen kommentarer:

Legg inn en kommentar